Review of R. Kent Crookston, Book of Mormon Ecology: What the Text Reveals about the Land and Lives of the Record Keepers (Provo, UT: Village Lane, 2020). 267 pages. $12.95 (paperback).

Abstract: As is well known, the Book of Mormon is a brief spiritual account from many centuries of Lehite and Jaredite peoples. Some of its authors mentioned that the book contains very little (not even 1%) of what happened, especially of non-spiritual matters. Nevertheless, from the tidbits of information found in the book, many have deduced or speculated on aspects of Nephite, Lamanite, and Jaredite life, including where the events took place. In Book of Mormon Ecology, R. Kent Crookston analyzes agricultural, ecological, and physical information in the Book of Mormon and proposes that its peoples lived in a Mediterranean climate, not in Mesoamerica. Seeds from Jerusalem growing well in America, seasons of grain and fruit, and east winds have good connections to Mediterranean climates. His analysis raises pertinent questions about Mesoamerican models. However, many conclusions have a weak basis or do not consider other evidence strongly correlated to a Mesoamerican setting, including ecological factors. For other details, reasonable explanations also fit a Mesoamerican model. A definitive post-oceanic locale of Book of Mormon peoples remains elusive and controversial because of meager non-spiritual information in the book, multiple plausible interpretations of non-spiritual words, and insufficient archaeological data throughout the Americas.

[Page 328]The location of Book of Mormon events has been of wide interest for many years. The locations of pre-oceanic-voyage events of the Lehite party are relatively uncontroversial. The general trip from Jerusalem to the Red Sea, along the eastern side of the Red Sea, inland across the southern part of the Arabian Peninsula, and then to the shore of the Arabian Sea, is well correlated with the Book of Mormon text.1 However, the American location of Book of Mormon events remains unknown.2

The post-voyage setting of the Book of Mormon, once thought settled as occurring in Mesoamerica, has now become hotly debated, as people parse the text, modern maps, Joseph Smith’s words, historical documents, and archaeological data for clues. Hindering the effort, ancient Book of Mormon place names were not retained into modern times (as occurred with many biblical locations), and the dearth of details in the book impedes a clear understanding of most aspects of the ancient people’s lives.3 The morsels of geographic information have enabled people to propose multiple locations. Mesoamerica has the most developed models, but locations in North America, South America, and even Asia and Africa have been proposed.

Into the debate over the post-voyage location comes a book by R. Kent Crookston, Book of Mormon Ecology.4 According to biographies available on the internet5 and comments made in his book [Page 329](p. xi), Crookston was educated in agronomy (bachelor’s degree) and plant physiology (PhD). He worked in academia where he researched physiology of photosynthesis; photosynthate partitioning and grain growth; and corn, soybean, wheat, and barley management. He did agricultural work in Morocco for many years. He consulted on agriculture in many places around the world. Therefore, he is well qualified to address agricultural and related topics. He notes that although the Book of Mormon authors did not provide detailed physical descriptions, “reading between the lines” and analyzing words give clues to physical aspects of the Book of Mormon peoples’ lives (p. xii). Based on his expertise and his analysis of the Book of Mormon text, Crookston argues for a setting in a Mediterranean climate.6

Having someone look at the Book of Mormon from a different perspective is a wonderful thing, and Crookston raises some important questions and highlights some valuable nature-spiritual insights. These points are beneficial. However, I find the Book of Mormon’s ecological, agricultural, physical, and related words too meager and ambiguous to suggest that Mediterranean-America was a more likely home of the Jaredites, Mulekites, Nephites, and Lamanites than Mesoamerica.

A Bounty of Natural and Agricultural Terms

As a person who loves gardening and nature, I value Crookston’s documentation of natural, agricultural, and physical terms in the Book of Mormon and how those relate to spiritual matters (for example, pp. 106, 120, 121, 127, 129). He notes that the people must have been familiar with agriculture and nature because these terms are used throughout the record to teach spiritual lessons. This familiarity allowed Book of Mormon prophets to effectively use these as metaphors in their spiritual messages. He separated terms used in spiritual ways from those used temporally or physically. For example, “a large and spacious field” in Lehi’s dream (1 Nephi 8:9, 20) served as a spiritual metaphor, and “many . . . fields of grain were destroyed” after a battle (Alma 3:2) describes a physical event (pp. 154–55). He documents dozens [Page 330]of terms that are used many times. Notably, this tally of terms excludes all those in the Isaiah chapters. He tallied Isaiah’s terms in an appendix.

Three general observations regarding the nature-spiritual connection were made (pp. 253, 259–61):

- “Although few of the natural world terms would be considered inherently spiritual,” 42% of uses of these terms were used in a spiritual context. (This is non-Isaiah usage.)

- Isaiah “drew almost completely from nature to enrich his writing.”

- “The Book of Mormon record keepers were interwoven with the natural world and called upon it repeatedly to strengthen their spiritual speaking and writing.”

These insights are helpful and edifying.

Crookston deduced an insightful example involving the descriptive term “wild flock.” Speaking of people who reject the Lord’s ways, two verses use this term:

Yea, they are as a wild flock which fleeth from the shepherd, and scattereth, and are driven, and are devoured by the beasts of the forest (Mosiah 8:21).

Yea, and ye shall be smitten on every hand, and shall be driven and scattered to and fro, even as a wild flock is driven by wild and ferocious beasts (Mosiah 17:17).

Normal Book of Mormon usage was just “flock” or “flocks,” but the Nephites apparently also had wild flocks. Crookston notes,

We’re left to wonder what [the wild flocks] might have been. Did the Nephites tend some of the undomesticated creatures of the country, perhaps deer, or . . . wild goats . . .? These creatures can be tamed, but still retain their feral impulses and can be most unpredictable when startled. In [Mosiah 8:21] the wild flock, for some reason, fled from the shepherd, who would probably have wanted to be their protector. In [Mosiah 17:17] the wild flock was scattered by wild and ferocious beasts. What excellent imagery to convey the status of people who, without any apparent provocation, fled from the good shepherd, or in the other case, were goaded from the paths of righteousness by the evil one himself, only to be overtaken by sin. (p. 106)

[Page 331]This is a beautiful example of how someone with a different perspective can help all of us gain more from the scriptures.

Nevertheless, the emphasis of Book of Mormon Ecology is not on spiritual messages from nature. The book’s focus lies on where Book of Mormon people lived—the geography of the Book of Mormon. In the next two sections, I present arguments Crookston gives in favor of his Mediterranean-American hypothesis. Next, I list important questions raised by Crookston. After these three sections, I present counterarguments.

Evidence for a Mediterranean-AmericanLocation for the Book of Mormon

Crookston’s thesis is that references to the agricultural, biological, and physical world in the Book of Mormon strongly suggest that the people lived in a Mediterranean climate. Crookston proposes that these natural-world and related terms do not justify a Mesoamerican location.

As he defined them, Mediterranean ecosystems are located on western coasts adjacent to cold ocean currents about 30º to 40º north or south of the equator. These ecosystems exist in the Mediterranean-Sea Basin, California, northwestern Mexico, central Chile, the Cape region in South Africa, southwestern Australia, and southern Australia. These ecosystems are pleasant areas for human occupation. Mediterranean climates typically have cool, moist winters and warm, dry summers (p. 4).

In great detail, Crookston lists and analyzes 108 agricultural, biological, and physical terms and their context and usage in the Book of Mormon.7 Thirty-five words show a significantly better match to Mediterranean-America than Mesoamerica: abundance, barley, bones, cement, dry, earth, famine, forests, fruit, grafted, grain, grapes, hill, horses, land, place, plains, plant (used as a verb), rain, river, seasons, seeds, sheaves, thirst, timber, trees, vine, vineyard, water, wheat, wilderness, wind, wine, wolves, and wood. Three words have moderate connection to Mediterranean-America and not to Mesoamerica: bread, serpents, and stone. Eighty words are neutral as to a location: animals, apparel, ass, beasts, bees, branch, calves, cattle, chaff, chickens, cloth, clothing, corn, cows, crops, cumoms, cureloms, dig, [Page 332]dirt, dogs, dragons, drink, dust, eat, elephants, fatlings, fevers,8 field, figs, firstlings, fish, flocks, fold, food, fowl, game, garden, goats, grass, ground, hail, harvest, heat, herds, honey, insects, lamb, linen, lion, meat, mist, mountains, neas, olives, oxen, pasture, pearls, plants (used as a noun), plow, prune, rock, roots, sand, sea, seashore, sheep, shepherd, sheum, silk, sow, storm, swine, tents, thistles, thorns, till, valley, vultures, waves, and wool.9 Crookston argues that no words are a weak fit for Mediterranean-America and eleven words—barley, bones, cement, dry, grapes, place, plant (verb), seeds, water, wheat, and wolf—do not fit Mesoamerica (p. 254).

From this analysis, I find the strongest arguments are in seeds brought from Jerusalem, interpretation of words, grains, aridity of the land, fruits, chaparral landscape, characteristics of the land northward, the east wind, tracking people, seasons, and wolves. These eleven items, addressed in the following sections, are relatively straightforward arguments from the Book of Mormon’s ecological, agricultural, and physical words.

Seeds from Jerusalem

Crookston’s analysis of the Book of Mormon began with an insight he had after completing his PhD in plant physiology. While reading the Book of Mormon, he noticed a potent agricultural message in events that occurred just after the Lehites arrived in the promised land. Nephi wrote,

And it came to pass that we did begin to till the earth, and we began to plant seeds; yea, we did put all our seeds into the earth, which we had brought from the land of Jerusalem. And it came to pass that they did grow exceedingly; wherefore, we were blessed in abundance (1 Nephi 18:24).

These seeds included grain and fruit “of every kind” (1 Nephi 8:1). Not only did the Lehites gather these seeds in Jerusalem, but Nephi also mentions four times that they took seeds with them (1 Nephi 8:1, 16:11, 18:6, and 18:24). So those seeds were important. Those seeds produced abundance after their arrival in the new land. With his agricultural and graduate-school background, Crookston deduced that wherever the Lehites landed in the New World, their landing site was a good fit for the Jerusalem seeds. Seeds grow best in a climate [Page 333]and latitude where the plant is acclimated. Therefore, he reasoned, Jerusalem-adapted seeds would grow best in a New World climate that was similar. Crookston explains well the reasoning behind this conclusion. Plants need the right soil and the right amount of cold and heat and light and darkness. Corn plants from Texas will not produce well if planted in Wisconsin and vice versa. Thus, he reasons, seeds from Jerusalem would grow best in the New World Mediterranean climates of southern California and Baja California or in coastal regions of central Chile (near Valparaiso). He states that Jerusalem-adapted seeds would not only fail or grow poorly in the acidic soils of tropical America but would also be susceptible to the alien plant blights and alien pests found there (pp. vii–viii, 3–8, 12–14, 60, 62–65, 147–51, 173).

Words as described

Crookston proposes that Book of Mormon ecological and related words mean exactly as we interpret those words today. Barley, wheat, oxen, cows, asses, horses, goats, and others were the same as we know those plants and animals today—like those from the Old World. Nephi distinguished domestic old-world animals from wild animals, suggesting he recognized the old-world animals and simply grouped all wild animals together: “we did find upon the land of promise . . . both the cow and the ox, and the ass and the horse, and the goat and the wild goat, and all manner of wild animals (1 Nephi 18:25). Crookston disagrees with those who propose that Book of Mormon people gave familiar names like cow and goat to animals that had some resemblance to what they remembered of those animals in their previous home. So few new-world animals were domesticated that the proposed substitute animals are unlikely to be in the herds and flocks of the Book of Mormon people. The difficulty in domesticating animals suggests, according to Crookston, that calling native American animals by Old World names may be inaccurate. He states, “an acceptance of all the text’s ecological words and descriptions, just as they appear, is much easier if we don’t attempt to force fit them into a Mesoamerican location but allow for the consideration of a Mediterranean eco-setting instead.” Although he acknowledges the possibility of mistakes and imperfect translations, Crookston states “we need not question whether those voices from the dust can be reliably understood by the modern reader” (pp. xiii–xiv, 20–25, 138).

[Page 334]Barley and wheat

Crookston says wheat and barley would grow readily in Mediterranean-America but not in Mesoamerica. Barley and wheat were important grains to the Book of Mormon people. Barley was used in Nephite commerce (Alma 11:7, 15). Barley and wheat were grown by Nephites who returned to the land of Nephi (Mosiah 7:22, 9:9). Barley may have been the most common grain because it was mentioned as part of their monetary system and “was a valued and sustainable commodity.” Barley is hardy and can grow in dry areas, cool or cold places, and in salty soils. It grows well in Mediterranean climates, “where it outperforms other cereals in the drier areas.” Barley is ill-suited to wet, tropical climates. It is usually not grown for food unless people must (when the environment is dry and the soil is salty). Crookston concludes that the presence of barley is incompatible with life in a moist tropical area such as in Mesoamerica (pp. 5, 31–37, 42, 52, 64–65, 78–79).

Dryness, droughts, and thirst

Characteristic of Mediterranean regions and uncharacteristic of Mesoamerica, Crookston argues that the Book of Mormon land was dry; water sources were limited. The place where Ammon and the servants of King Lamoni watered the king’s flock was called Sebus (Alma 17:26–39; 18:1–7). The king’s servants would have gone to a different watering place if they could, so they would not risk their lives having to confront plunderers who would steal their flocks. The land northward was remarkable for its plentiful water. Because the land northward was described as having “many rivers” and “many waters” (Helaman 3:3–4; Mosiah 8:8; Mormon 6:4) and no rivers are mentioned for the land of Nephi, the land of Nephi was likely relatively dry. Otherwise, why would the many waters be noted? Two major droughts are described in the Book of Mormon: one for the Jaredites (Ether 9:28–35) and one for the Nephites and Lamanites (Helaman 11:2–18). The latter drought lasted three years. Droughts are common in Mediterranean climates, but “severe drought is comparatively uncommon in Mesoamerican lands, and a relentless drought lasting three years would be very unlikely.” In the Book of Mormon, Nephites who went to the Lamanites (Mosiah 7:16; Alma 17:5), who were needy (Alma 4:12), who were in prison (Alma 14:22; 20:28–29), and who were at war (Alma 60:3) experienced thirst. Thirst would be more likely in an arid, Mediterranean climate than in Mesoamerica, where “streams and rivers were readily available.” Thirst would be especially common [Page 335]during the Mediterranean dry season (pp. 142–44, 149–51, 152–54, 174, 191, 193, 220–23, 225–33).

Fruits

Fruit-growing in the Book of Mormon strongly suggests a Mediterranean region, according to Crookston. Only three fruits are mentioned by name in the text: figs, grapes, and olives. These are important fruits in lands around the Mediterranean Sea. “The frequent mention of wine in the text clearly suggests grapes,” which “are seldom grown in the tropics,” he notes. Fruit, and grain, “of every kind” is typical of the great diversity of plants in Mediterranean regions of the world. He notes that today the Mediterranean regions of California, Chile, and Peru provide United States markets with abundant “fruit of every kind.” Fruit grew again after the Jaredite and Lehite droughts. “Renewal of fruit growth” at the end of a great famine “matches what one would expect in a Mediterranean climate.” Grafting of olives, grapes, and figs was, and still is, common in the Mediterranean Sea region (pp. 43, 46–48, 49–50, 52–53, 58–59, 60, 75–78, 79–81, 173).

Sporadic trees and chaparral

Crookston finds several Book of Mormon statements compatible with a chaparral landscape:

- The Place of Mormon had a fountain of pure water near a thicket of small trees, and wild animals frequented the area at times (Mosiah 18:4–5). Regions where “sporadic thickets of small trees flourish is shrubland” or chaparral, distinctive of Mediterranean landscapes. The seasons when the Place of Mormon was infested by wild beasts likely would be dry times when animals would come to a spring for water. Mediterranean-America has such seasons.

- On their journey through the New World wilderness, the Lehites noted “beasts in the forests of every kind”—including cows, oxen, horses, asses, goats, wild goats, and “all manner of animals” (1 Nephi 18:25). The mentioned creatures would need grass, which would be allowed by a landscape with intermittent forests or shrubland.

- Enos went to hunt beasts in the “forests” (Enos 1:3). King Limhi’s army hid in “the forests”, not “the forest.” These forests were “separated or sporadic areas of trees” or “more than one forest.”

- [Page 336]Kings Noah and Limhi could look out from a tower and see the approaching Lamanite army because their surroundings were not a dense subtropical jungle. (Mosiah 11:12; 19:5–6; 20:7–8). If the region were dense forest, Noah and Limhi would not have been able to see the Lamanite army.

- Plains were mentioned during four battles in Nephite or Jaredite territory (Alma 52:20, 62:18–19; Ether 13:28–29, 14:15–16). Plains are more likely to have been found in Mediterranean-America than in jungle-prone Mesoamerica. Another battle likely occurred in an open area (Alma 43:31–52). When Helaman and his 2,000 warriors were being chased by a Lamanite army (Alma 56:30–44), the chase most likely took place in an open area where the armies could see each other, not heavy forest.

Therefore, Crookston deduces the descriptions are a better fit with chaparral or sporadic, patchy Mediterranean forests than dense-jungle Mesoamerican forests (pp. xv–xvi, 43–46, 70–73, 75, 164, 173, 186–90, 205).

Bones and trees in the Land Northward

A search party sent by King Limhi found a previously populated land covered with human and animal bones and ruins of buildings; the land also had many waters (Mosiah 8:8; see also Omni 1:22, Mosiah 21:26, Alma 22:30). Later, people migrated to this northward land, which “was covered with large bodies of water.” A significant part of the land had little timber (Alma 50:29, 63:4–9; Helaman 3:3–11). The bones discovered in the land northward were hundreds of years old. Finding bones this old is more congruent with a dry climate than the much wetter Mesoamerican climate where bones as well as flesh disintegrate quickly, Crookston notes. This northern land was very dry, “and there must have been very little vegetation.” The lack of trees provides further evidence, Crookston argues. “The disappearance of trees, followed by their extended absence, with a struggle to reestablish them, is characteristic of a Mediterranean-desert ecology.” Trees are difficult to reestablish in Mediterranean eco-zones. For example, in the Mediterranean Sea Basin, efforts to restore cedars of Lebanon and Atlas cedars in Morocco “have proven very challenging” (pp. 94–95, 134–40, 166–72, 180–81, 232–33).

[Page 337]East wind

Abinadi and Limhi mentioned reaping the east wind because of wickedness (Mosiah 7:31, 12:6). “Destructive east winds are common in Mediterranean climates,” Crookston states. For example, blowing from deserts to the east, east winds plague Jerusalem, Egypt, Morocco, southern California, and northern Baja California. Thus, these winds are a good fit for a Mediterranean-American homeland for Book of Mormon people (pp. 172–73, 246–48).

Tracking people and getting lost

In the wilderness, some people became lost, could not follow the tracks of others, or both.10 Tracking animals and people through a thick jungle is easier than tracking in an arid chaparral region. In the jungle, broken foliage makes tracking easy. For instance, how could escaping Nephites lose the people following them if travel was through a jungle, and especially with Nephite flocks and herds?11 Crookston proposes that an arid Mediterranean climate can be a place where people become easily lost and where tracking can be difficult (pp. 240–43).

Separate seasons of grain and fruit

Crookston notes that distinct seasons for grain and fruit are suggested in Helaman. At the end of a drought, the book reports that after the Lord sent rain, the earth “did bring forth her fruit in the season of her fruit. And it came to pass that it did bring forth her grain in the season of her grain” (Helaman 11:17).12 Mediterranean regions have distinct seasons of grain and fruit—one of each per year. These seasons may overlap but are at different times of the year. In Guatemala, representing Mesoamerica, corn (maize) has three seasons per year; “thus, the season of grain . . . is not a good way to describe a Guatemalan [Page 338]cropping system. . . . In the tropics . . . fruits are harvested at different times throughout the year, depending on the species” (pp. 51–52, 204–9).

Wolves

Wolves are mentioned twice in the Book of Mormon text (Alma 5:59–60, 3 Nephi 14:15). Crookston mentions that wolves are not known to have lived in Mesoamerica but were found from present-day Mexico City north, including all present-day California and northern Baja California (pp. 129–30).

Countering Strong Mesoamerican Arguments

The Mesoamerican model is supported by convincing evidence. Evidence of large ancient cities is found in Mesoamerica but not in California. Cement structures appeared in the proposed land northward consistent with the Book of Mormon record.13 The land northward’s many waters (Helaman 3:3–4, Mosiah 8:8, Mormon 6:4) are a good fit for southern Mexico but not for the dry deserts in northern regions of southern California (figures 1 and 2). Mesoamerican volcanic eruptions are plausible explanations for the great destruction mentioned in the Book of Mormon before Christ’s appearance (3 Nephi 8:5–25, 9:1–12) and have been dated to that period.14 Crookston provides explanations for these four points that, he argues, make his Mediterranean-American model plausible.

[Page 339]

Figure 1. Biomes in the Baja California Region. Eight defined biomes (major habitat types) in Baja California and surrounding regions are represented by color (inset large box). Within each biome, black lines separate ecoregions, which are designated by individually boxed names. Rivers and lakes are shown in dark blue and reservoirs in light cyan (inset large box). The Gila and Colorado Rivers are labeled. Also labeled are six modern cities (Tijuana, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Yuma, Nogales, and Hermosillo). *The Sierra Madre Occidental Pine-Oak Forests have also been classified as Tropical and Subtropical Coniferous Forest. See appendix B for definitions of the biomes. Sources: Biomes and ecoregions: see appendix B. Rivers: Bernhard Lehner and Günther Grill, “Global River Hydrography and Network Routing: Baseline Data and New Approaches to Study the World’s Large River Systems,” Hydrological Processes 27 (2013): 2171–86, hydrosheds.org/products/hydrorivers. Lakes and reservoirs: Mathis Loïc Messager et al., “Estimating the Volume and Age of Water Stored in Global Lakes Using a Geo-Statistical Approach,” Nature Communications 7 (2016): 13603, hydrosheds.org/products/hydrolakes.

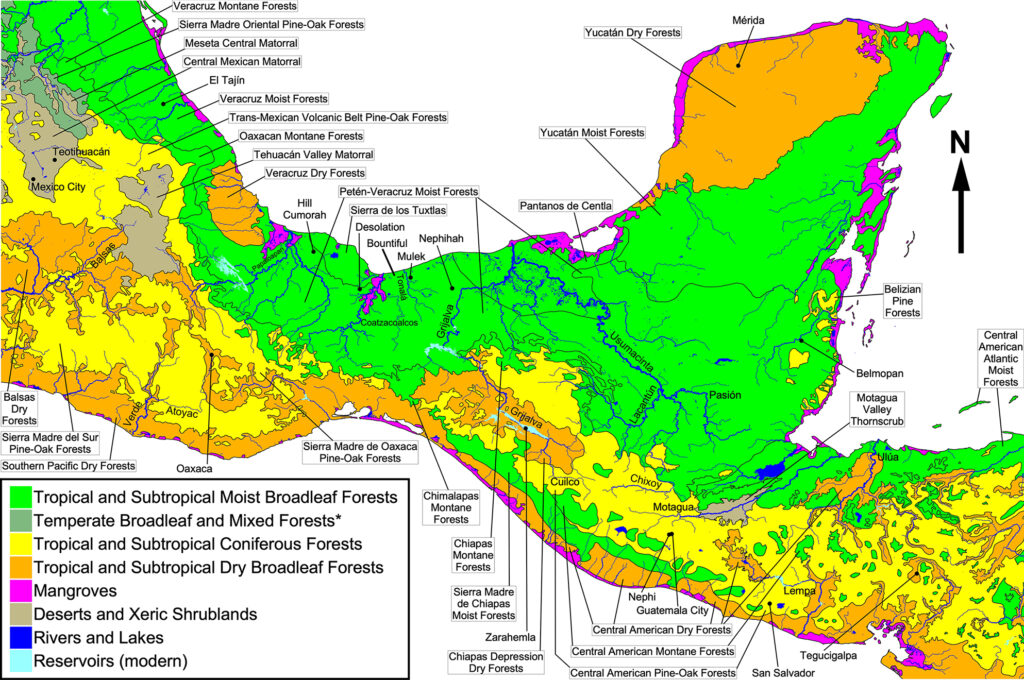

[Page 340]

Figure 2 (opposite page). Mesoamerican Biomes. Six defined biomes (major havitat types) in Mesoamerica are represented by color (inset large box). Within each biome, black lines separate ecoregions, which are designated by individually boxed names. Rivers and lakes are shown in dark blue and reservoirs in light cyan (inset large box). Some rivers are labeled. Also labeled are seven modern cities (Mexico City, Oaxaca, Mérida, Guatemala City, Belmopan, Tegucigalpa, San Salvador), two archeological sites (Teotihuacán and El Tajín), and six proposed Book of Mormon locations (Zarahemla, Nephi, Nephihah, Mulek, Desolation, Bountiful, and Hill Cumorah). Bountiful is predicted to be near the coast and between the Coatzacoalcos and Tonalá Rivers or near one of these rivers. Teotihuacán and El Tajín are archaeological sites where ancient cement structures were discovered and date to Book of Mormon times. Mulek, Nephi, and Zarahemla correspond to archaeological sites known as La Venta, Kaminaljuyu, and Santa Rosa, respectively. *The Sierra Madre Oriental Pine-Oak Forests have also been classified as Tropical and Subtropical Coniferous Forest. Sources: Biomes and ecoregions: see appendix B. Rivers: Lehner and Grill, “Global River Hydrography and Network Rrouting,” 2171–86. Lakes and reservoirs: Messager et al., “Estimating the Volume and Age of Water Stored in Global Lakes,” 13603. Book of Mormon locations: Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex 22, 131–32, 142–43, 322, 538–39, 614–15, 632, 688, and maps 4, 8, 9, 10; John L. Sorenson, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 241; Ethan Lloyd, email correspondence with author, Spring 2025.

The lack of archaeological ruins in American Mediterranean regions should not be taken as evidence that people did not live there. Crookston notes that the Book of Mormon does not mention that buildings were made of stone—the common building material found in ruins of Mesoamerican civilizations. The only mention of stone is that it was used for defensive fortifications (Alma 48:8). He asks, when the Lord caused fire to be in the prison where Nephi and Lehi were [Page 341][Page 340]held (Helaman 5:20–44), why does the record mention that the walls did not burn (verse 44) if the walls were made of stone? If buildings were not made of stone or only had stone foundations, the principal building material was wood, he argues. Wood, of course, eventually decays and disappears. We should not expect to find today much from ancient wooden structures. In Greece today, Sparta has very little remaining that testifies it was a great city—more powerful than Athens after Sparta defeated Athens in the Peloponnesian War. Yet, Athens retains many more ancient remains than Sparta does (pp. 81–86, 193–94, 209–16).15

Book of Mormon cement was not concrete. The Book of Mormon mentions that cement was used for buildings because wood was scarce (Helaman 3:7, 9, 11), but the scarcity of timber suggests the people did not have enough wood to calcine lime, necessary to [Page 342]make concrete-like cement (a pasty substance that can be easily molded and then hardens into a stone-like mass). Therefore, cement, Crookston argues, could refer not to concrete-like construction but to rammed earth or compressed dirt. This is used in Morocco and elsewhere and is called cement. Subsoils containing clay along with sand and perhaps small stones are placed in forms and aggressively compressed in layers. The mixture is moist when rammed. The same method is used to place additional layers on top of earlier ones. After the rammed earth dries, the result is like sandstone and has a durability much like concrete. Morocco contains hundreds of centuries-old, rammed-earth buildings. Similar construction has been made from cob or adobe, such as the adobe Taos Pueblo in the southwestern United States (pp. 134–40).

As for “many waters” in the land northward, Crookston notes (1) that plentiful water does exist in some dry climates and (2) the possibilities of lakes in California that are no longer present. The Colorado, Nile, and Euphrates Rivers all end in Mediterranean-climate regions and provide plentiful water in these dry places. Ancient Lake Cahuilla, formed by the Colorado River in southern California’s Salton basin area, “apparently persisted until about A.D. 1600.” He suggests this lake and perhaps others may have been present in Book of Mormon times (p. 169).

As a possible cause of the “mists of darkness,” storms, and so forth linked to volcanic activity by geologists, Crookston notes evidence that the Salton Buttes volcano cluster in the Imperial Valley in southern California erupted 2,000 years ago. This is approximately the same time as mentioned in the Book of Mormon and when volcanic activity also was found in Mesoamerica. He also suggests the mixture of fog and dust that occurs in Arabia might also be like what occurred in Book of Mormon times (pp. 181–84).

Based on the physical, agricultural, and ecological data, Crookston argues that Mesoamerica should be reassessed and that Mediterranean-America should be investigated further (p. 256).

As a fellow scientist, I appreciate that Crookston described his idea as a hypothesis. That is the correct word. Model is also a good word. As Crookston demonstrated, the word theory should not be used. In scientific terminology, theory means a well-established idea, but in common parlance, theory is often used as a synonym for hypothesis.

[Page 343]Important Questions

With respect to Book of Mormon peoples living in Mesoamerica, Crookston’s thesis stimulates several important questions:

- If the Lehites landed in Mesoamerica, what could account for their Mediterranean-Jerusalem seeds growing well (1 Nephi 18:24)?

- Do the words barley and wheat (Mosiah 7:22, 9:9; Alma 11:7, 15; 3 Nephi 18:18) refer to Old World or New World grains?

- Clearly, barley and wheat grow well in Mediterranean climates, but can these grains be grown in Mesoamerica?

- Were any native American animals domesticated or semi-domesticated by ancient people?16

- What do we make of the fact that stone is not mentioned as a building material in the Book of Mormon, except for a fortification wall? (See pp. 81–86, 136, 193–94, 209–16.)

- If the Jaredites lived in Mesoamerica, which is damp and humid, how could their bones still be present presumably hundreds of years (>400 years) after the Jaredite civilization destroyed itself? (See pp. 94–95, 166–68.)

- Given that unexcavated Mayan ruins today are engulfed by jungle, why would trees still be scarce in the “land northward” (Helaman 3:3–11) if Mesoamerica was the location and hundreds of years had passed?

- If trees were scarce and wood was needed to fire kilns to make cement, where did Book of Mormon people get the wood? (See pp. 134–40.)

- What was the land of Mesoamerica like when ancient people (Olmec, Maya, and so forth) lived there?

Answers to these questions should be answered or sought by those proposing Book of Mormon people lived in Mesoamerica.

Counterarguments

I agree with Crookston that many of his reasonings fit a Mediterranean-American location for the Book of Mormon, but I disagree that Mediterranean-America is the only likely or the best overall interpretation. Other interpretations also can be made that are consistent with [Page 344]a Mesoamerican location. And, he also interpreted words differently from common, modern definitions and ignored ecological evidence not in favor of Mediterranean-America. Other arguments are weak, confusing, inconsistent, or unjustified. The following counterarguments answer some of the noteworthy questions Crookston’s thesis raised and prompt significant questions that should be answered for the Mediterranean-American model. The lack of ecological detail in the Book of Mormon prompts many other questions and prevents making strong correlations between the book and particular ecosystems.

Word definitions

An important part of Crookston’s thesis is that Book of Mormon words should be defined with common, standard English definitions. For example, a cow is the old-world domesticated animal raised for milk and meat (Bos taurus). But a principal reason for defining words this way has an incorrect basis, and he did not use standard definitions consistently.

In large part, Crookston bases his assertion—that we can define words literally—on a statement he mistakenly attributes to Joseph Smith. The statement, as quoted by Crookston, reads, “The ancient record . . . brought forth from the earth as the voice of a people speaking from the dust, [was] translated into modern speech by the gift and power of God as attested by Divine affirmation.” Because the Book of Mormon was “translated into modern speech,” Crookston concludes that Book of Mormon word meanings are as a modern person, or a person in the 1800s, would understand them (pp. xii–xiv). The statement, though, is not a quote from Joseph Smith. The statement was written by the author or authors of “Origin of the Book of Mormon” in the introductory pages of the 1920 edition of the Book of Mormon.17 The statement was reprinted in the 1981 and 2013 editions of the Book of Mormon.18 The confusion appears to be because the statement follows a long quote of Joseph Smith’s account of the Book of Mormon origin. However, Joseph Smith’s words are in quotation marks. Editorial comments precede and follow the Joseph Smith quotation.

Crookston asserts fidelity to standard definitions but then does not with the word cement. He says compressed dirt “is often referred to [Page 345]as cement” (p. 139), but this is not a standard definition. The Oxford English Dictionary does not include rammed earth or compressed soil in its ten definitions.19 Therefore, if one can call compressed dirt cement, one could also call a deer a cow or a horse, as suggested by those who think the Book of Mormon immigrants attached names of familiar animals from the Old World to those they now saw in their new home in the New World.20

Likewise, one definition of the land also is not consistent with modern language. Crookston described the land of Nephi as chaparral or shrubland, a common feature in Mediterranean climes. Chaparral may have intermittent stands of trees, but the dominant plants are shrubs, not tall trees (pp. 70–72). Yet, the Book of Mormon says forest. Nephi said, “as we journeyed in the wilderness, that there were beasts in the forests of every kind” (1 Nephi 18:25). The Jaredite record says, “the land [southward] was covered with animals of the forest” (Ether 10:19). If it were Mediterranean chaparral, why was forest used to describe the wild landscape and not something more fitting to a chaparral ecosystem? If forest is a substitute for chaparral or shrubland, then Crookston [Page 346]is guilty of the same thing he accuses advocates of a Mesoamerican geography of doing.

One cannot assume Book of Mormon words have the common definition of today or even of Joseph Smith’s day. Defining many of these words requires work. Some meanings will change as new knowledge is obtained. For example, older English, not Joseph Smith’s native 1800s usage, was often found in his original translation. The work of Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack has shown that much of the language of the translated text follows Early Modern English usage (late 1400s to 1700) and not 1800s English usage.21

River Sidon

Crookston proposes that the River Sidon was a small river. He says it likely originated as a spring, rather than tributaries because the text mentions its head. “Spring-fed rivers are usually relatively small, and the Sidon could not have been a very large river” because, he said, a Lamanite army was “able to quickly cross it” during a battle (pp. 192–93).

These reasons are weak for suggesting the River Sidon was a small river. Could not a river start small with a spring and then be fed by tributaries or other springs to make the river large? The Book of Mormon text does not say crossing the Sidon was easy or difficult, fast or slow. In the account of the battle cited by Crookston, one crossing was started before the battle (Alma 43:35) and a second crossing was done during the battle as Nephites drove the Lamanites into the river (Alma 43:40). The first crossing may have been done at a relatively shallow place, but the second could have been at a deep or shallow place. When under attack, with the river being the only potential place of safety, soldiers would swim if necessary to escape!

Crookston did not mention one aspect in the text that indicates the River Sidon was large enough to carry many human bodies. The Book of Mormon records,

And now as many of the Lamanites and the Amlicites who had been slain upon the bank of the river Sidon were cast into the waters of Sidon; and behold their bones are in the [Page 347]depths of the sea, and they are many. (Alma 3:3, see also Alma 2:34)

And it came to pass that they did cast their dead into the waters of Sidon, and they have gone forth and are buried in the depths of the sea. (Alma 44:22)

These verses come after two battles that occurred along the River Sidon. In both cases, bodies were “cast into the waters of Sidon” and the bodies ended up in the sea. Bodies were not cast into a small river or dry riverbed where they could clog the channel and wait to be washed out to sea with the next massive rainstorm (and where the bodies would stink horribly in the meantime). Clogging the channel could create flooding when the river backed up and when rain came. The text says bodies were cast into water and were carried out to sea. This indicates a much larger river than that suggested in Book of Mormon Ecology. This aspect of the River Sidon should have been addressed.22

Large population

The Book of Mormon suggests large human populations (appendix A). Multiple verses mention people multiplying, people spreading over all the face of the land, thousands of converts, Lamanites more numerous than Nephites, land covered with buildings and cities, and people too numerous to count or as numerous as the sands of the sea.

Perhaps most telling are war reports. For example, a group of 2,000 soldiers is called a “little force” or a “small force” (Alma 56:17; 58:8, 12). Accounts of battles mention thousands of dead and “great slaughters.” In a Nephite civil conflict where many Nephites died and Amlicites were slain “with great slaughter,” the total dead were 19,094 (Alma 2:16–19). Immediately after this conflict, the Amlicites joined the Lamanites and both attacked the Nephites. After counting the dead in the previous conflict, now the record states the number of Nephite dead was uncounted “because of the greatness of their number” and states many Lamanites and Amlicites also died (Alma 3:1–3). This suggests significantly more than 19,000 total deaths. “Not many [Page 348]days” later, the Lamanites come again, and still the Nephites send “a numerous army against them” (Alma 3:20–23). Similarly, within short times after other heavy losses (one year and six years, for example),23 the Lamanite army returned to fight the Nephites with another massive army, and the Nephites could still defend themselves. In the final Nephite-Lamanite battle at Cumorah, the record mentions 230,000 dead (Mormon 6:10–15), and immense casualties were found in earlier battles during the last Lamanite-Nephite war. For the Nephites to have lost so many in the final battle, the opposing (Lamanite) army must have been at least twice that size.24 That is a massive army suggesting that the overall pre-war population of Nephites and Lamanites was in the millions. Before the final Jaredite battle, the Jaredite record mentions that the “whole face of the land was covered with the bodies of the dead” (Ether 14:21) and that two million men (of Coriantumr’s people) had been killed, plus “their wives and their children” (Ether 15:2). The final battle likely also must have resulted in many deaths because each army took four years to gather all the people to the battle site (Ether 15:12–15).

Anciently, could Mediterranean areas in North or South America have supported such a large population? Would not the area be decimated, especially when the people became extremely wicked, when, as in modern times, short-term gains would outweigh long-term sustainability? Crookston mentions the devastation that occurred anciently to stands of Atlas cedars (in Morocco) and cedars of Lebanon (pp. 171–72). Would not Mediterranean-America suffer the same devastation and more with the high population that the Book of Mormon record indicates was present? Baja California is primarily desert (figure 1); only a small part has a Mediterranean climate. Desert lands would be even more sensitive to abuse by large populations. Although some have questioned the accuracy of Book of Mormon population numbers, archeological data from Mesoamerica is consistent with a large ancient population.25 For example, recent LiDAR (light [Page 349]detection and ranging or laser imaging, detection, and ranging) studies show large cities underneath much of the current Mesoamerican forest. Archaeological evidence of large, ancient populations has not been found in Baja or Southern California.

Jungle, biomes, and forests

One of Crookston’s most forceful arguments is that many situations and wordings do not make sense for a jungle (pp. xv–xvi, 43–46, 70–73, 75, 164, 173, 186–90, 205, 240–43). Because having to cut paths through thick undergrowth makes tracking easy, could a group being chased in ancient Mesoamerica lose their pursuers, as occurred for Limhi’s people (Mosiah 22:15–16)?26 Did ancient Mesoamerica contain land that would be considered plains (Alma 52:20, 62:18–19; Ether 13:28–29, 14:15–16)? Was water always plentiful wherever people were, so that thirst was rare?27 Known biomes (major habitat types) and ecological regions also suggest questions about Mediterranean-American and desert regions of Baja California (see figure 1 and appendix B).

Mesoamerica has a varied landscape. Characteristics include coastal plains, lush vegetation, mountainous terrain, volcanic highlands, cenotes, arid regions, and rivers.28 A view of ecological regions [Page 350]and biomes in Mesoamerica (figure 2) shows that much of the Mesoamerican region is not thick jungle. Besides mangrove regions along the coasts, Mesoamerica contains four biomes ranging from wet to dry: tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests, tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests, tropical and subtropical coniferous forests, and deserts and xeric shrublands (figure 2). The designations of ecoregions and biomes do not mean all natural land is that designated type. “Ecoregions reflect the best compromise for as many taxa as possible. . . . Most ecoregions contain habitats that differ from their assigned biome.”29 In addition, much land has been converted into agricultural, residential, and other human uses.

In addition to variations within an ecoregion, the general definitions of these four biomes (appendix B) suggest that people being chased through Mesoamerican wilderness could indeed lose their pursuers. Thick underbrush is stated only for tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests where bare trees in the dry season facilitate growth on the forest floor by allowing sunlight to reach the floor. In the moist broadleaf and coniferous forest biomes, the canopy shields sunlight from the forest floor. John Sorenson’s model of Book of Mormon lands puts the Lamanite city of Nephi near present-day Guatemala City and the Nephite city of Zarahemla along the Grijalva River (figure 2). Between the two cities, the predominant biome is tropical and subtropical coniferous forest, which generally has “little underbrush.” Only around Zarahemla do we find a biome that typically has thick underbrush (tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests). Therefore, people could escape Lamanite lands without creating obvious trails through thick underbrush. Other Mesoamerican models have different placements of settlements, but according to the general definitions of the biomes (appendix B), thick underbrush would not be found throughout Mesoamerica.

Mesoamerican areas with coastal plains and sabana grasslands have been correlated to Book of Mormon settlements. A Nephite-Lamanite battle mentions plains between the cities of Bountiful and Mulek and a Nephite army marching “near the seashore” (Alma 52:18–22). Extensive plains lie between John Sorenson’s proposed sites of Mulek and Bountiful, near the Bay of Campeche (figure 2). Sorenson [Page 351]proposed “dry sabana grasslands of interior Tabasco” for the plains of Nephihah (Alma 62:18–19; figure 2). Plains mentioned in the Jaredite record (Ether 13:28–29; 14:16) could be in south-central Veracruz.30

Regardless of the nature of the native forests near ancient American settlements, the following eight reasons suggest dense forests were not necessarily everywhere if Book of Mormon people lived in Mesoamerica and suggest Mesoamerican forests could be a better fit to the Book of Mormon text than Mediterranean forests:

- Like today, trees would be cut down for timber to build houses and buildings and to clear land for cities, homes, and agriculture.

- Like today, perhaps large areas of forest were cleared for agriculture because the soil’s fertility was exhausted rapidly, as occurs with slash-and-burn agriculture.

- As stated previously, populations of Book of Mormon peoples were large. Large numbers of people would require large areas of land to live and grow food. Therefore, large numbers of trees and large areas of forest would have been cut down.

- A large population would require lots of trees for wood. After many people moved north where trees were scarce, timber was shipped to the land northward, indicating that wood was not scarce in the south (Helaman 3:10). Only relatively small areas are designated as forest biomes in Baja California (Sierra Juarez and San Pedro Martir Pine-Oak Forests, figure 1). Could these forests or other trees in the Mediterranean Forests, Woodlands, and Scrubs biome and Deserts and Xeric Shrublands biome support a massive population and allow exports to the north? Certainly, trees in Mesoamerica would grow back faster than Mediterranean-area trees and would avoid the problems with replenishing Mediterranean trees identified by Crookston (pp. 170–72). Therefore, Mesoamerican forests enable a more sustainable place for large wood-consuming populations than Mediterranean-America.

- In the land of Nephi, kings Noah and Limhi used a tower to view approaching Lamanite armies (Mosiah 11:12; 19:5–6; 20:7–8). If natural clearings were absent, artificial clearing [Page 352]of forests for agriculture, housing, and timber would have allowed these two kings to see the approaching army.

- The Book of Mormon uses the word forests three times and the word forest six times. Crookston argues the use of forests is more congruent with patchy groups of trees as are found in the chaparral landscapes of Mediterranean climates (pp. 43–46). However, perhaps, the forest in an area was fragmented naturally or artificially. Even if continuous, the forest on one side of a settlement could have been known by one name and the forest on the opposite side by another name. Perhaps a geologic feature such as a ridge or river denoted a separation of two named forests.

- The Book of Mormon does not say that thickets of small trees were common.

- Except for extensive stands of trees that exist or have existed in Mediterranean climates, forests are better correlated with Mesoamerica than a Mediterranean climate (pp. 43–46, 66–75). Natural Mesoamerica has more trees than natural Mediterranean-America.

Perhaps Book of Mormon language is consistent with large stands of trees in Mediterranean-America, but the words are also compatible with Mesoamerican forests, especially if, as today, a large human population is present and much of the forest has been cut down.

A look at the ecosystems of the Baja California region (figure 1) and the Book of Mormon text stimulates questions about the “land northward.” The Book of Mormon says this land had “large bodies of water and many rivers,” and “many waters, rivers, and fountains” were present (Mosiah 8:8, Alma 50:29, Helaman 3:4, Mormon 6:4). The record also says some trees were in this land and others had been cut down (Helaman 3:5–6). Where would the many rivers and fountains be in Mediterranean-America? Did the Lake Cahuilla area also have many rivers and fountains? According to Crookston, the lake was formed by meanderings of the Colorado River (p. 169). What other rivers were part of this land? Would one need to look farther north? Anciently, were any trees present in the proposed Mediterranean land-northward?

Alternative interpretations

The lack of detail for many passages in the Book of Mormon means that these words can be interpreted more than one way. The interpretations consistent with Mediterranean-America are one [Page 353]possibility, but none of the following seven examples definitively rule in Mediterranean-America and rule out Mesoamerica. This is true for even some of Crookston’s strongest points.

Although droughts are common in Mediterranean climates and uncommon in Mesoamerica (pp. 142–44, 149–51, 152–54, 174, 191, 232–33), the Book of Mormon’s explanation of the Jaredite (Ether 9:28–35) and Nephite-Lamanite (Helaman 11:2–18) droughts could be taken to favor Mesoamerica. As described, the Book of Mormon droughts seem to be rare events. (Of course, if droughts were common, other ones not tied to heavenly censure may have been left out.) Jim Hawker’s intriguing analysis of stalagmites in three Mesoamerican caves, noted by Crookston (pp. 143–44), showed that a multiyear drought did occur there consistent with the time of Helaman 11.31 Yes, famine is more common in Mediterranean-America, but that does not rule it out in Mesoamerica.

“All the Lamanites” took flocks to drink from “the water of Sebus” or “the waters of Sebus” and some Lamanites plundered other Lamanite flocks from this place (Alma 17:26, 18:7). Certainly, this could describe a watering place in a Mediterranean climate (pp. 225–33). But is this clime the only possibility? Was Sebus a small watering place like a pond or spring? Was Sebus a larger body of water, such as a river, stream, or lake? Definitions of water or waters are consistent with either small or large.32 The text does not define the waters. [Page 354]Elsewhere, the “waters of Mormon” (Mosiah 18:5, 8) are defined as a fountain, which suggests a spring (p. 231), and the “waters of Sidon” are defined as a river (Alma 2:34; 3:3; 43:40, 50; 44:22; Mormon 1:10). If the waters of Sebus were large, the plundering gang could be spying on the group and may have confronted them wherever they went to give the animals water (Alma 18:7). If the incident occurred during the Mesoamerican dry season or other watering places were far away (as the text strongly suggests), then, indeed, regardless of climate, King Lamoni’s servants would likely be required to go to Sebus, regardless of its size. Both Mediterranean-American and Mesoamerican interpretations are possible. Indeed, this could fit other climates, too.

Crookston’s interpretation of separate seasons of fruit and grain fits nicely with a Mediterranean-American model (pp. 51–52, 204–9), but is that interpretation the only possible one? Why are we limited to one season per year for each crop? Yes, in Mesoamerica fruits ripen at different times of the year, but even in Mediterranean climates, fruits ripen at different times throughout its “season of fruit,” depending on the type of fruit. Could the season of fruit and season of grain simply be figures of speech, a form of parallelism, used for emphasis? Could the two seasons refer to individual types of fruits and grains growing whenever it was their time?

The assumed open landscape is not necessary for a multiple-day chase and battle involving Helaman and 2,000 sons of converted Lamanites, another part of the Nephite army, and a Lamanite army sandwiched between the two Nephite armies (Alma 56:30–54). Crookston states, “plains are not specified,” nevertheless, the long chase “was obviously [in] an expansive open area, not forest or jungle.” Also, “the country was open enough for the armies to see each other” (pp. 189–90). However, Helaman’s group could not see that the Lamanite army was fighting the other Nephite army. Helaman’s army only returned when they realized they were no longer being pursued [Page 355]and feared the Lamanites would overpower the other Nephites. How could they have not seen the two armies fighting if they were in open country? Why could not the chase and battle have been in a forest?

The connection of wickedness to common and destructive east winds (Mosiah 7:31, 12:6) of Mediterranean climates is intriguing (pp. 172–73, 246–48), but is it definitive enough to place Book of Mormon people there? Does the east wind prophecy suggest a common or uncommon event? Does the prophecy mean an east wind as in Mediterranean climates or any windstorm from the east? Crookston noted that less common “east” winds do occur in Mesoamerica (pp. 247–48).33 In addition, could east wind refer to hurricanes, which would generally come from an easterly direction on the Atlantic side or would come from the east as the counterclockwise winds at the leading edge made landfall on the Pacific side? Hurricanes do occasionally strike Mesoamerica. Again, either location fits the scriptural record.

In terms of people being lost, both Mediterranean shrubland (pp. 240–43) and Mesoamerican forest are good candidates. Dense forest, where one can only see a few trees ahead and trees often look the same from any viewpoint, is a place where people can easily lose their bearings and become lost. Indeed, people may get lost almost anywhere—especially without landmarks or trails.

Population growth statements have ambiguity. Crookston suggests that Book of Mormon recordkeepers lived in a Mediterranean climate but that descendants, relatives, or friends moved elsewhere, such as to Mesoamerica. “The friends of Jared and his brother . . . began to spread upon the face of the land, and to multiply” (Ether 6:16, 18). Crookston argues that the friends separated from Jared and his brother, we have no record of them, and “we can only imagine to where they might have journeyed and settled” (pp. ix–x). Yes, that is one possible interpretation. Another interpretation of those verses and others (Ether 6:16–21) is consistent with the twenty-two friends and their families remaining part of the Jaredite nation with some Jaredites moving out to an unpopulated, but nearby, land as the population grew.34 The [Page 356]latter interpretation is more consistent with other verses in the Book of Mormon that mention Nephites and others spreading out over the land, with no indication that the people became a new nation or went far away (Jarom 1:5–6, Mosiah 27:6–7, see also appendix A, cf. Alma 63:4–8, Helaman 3:3–4).

Alternative interpretations from the Book of Mormon’s meager non-spiritual details mean a person must be careful with his or her assertions and patient with those of others. A single description may fit multiple locations or situations.

Seeds from Jerusalem growing well in the New World

The abundant growth of seeds from Jerusalem (1 Nephi 18:24) is the strongest evidence that the Lehites landed in a similar American climate, but does this rule out any other location? If they settled in Mesoamerica, did the seeds grow well because of the tilling and aeration of undisturbed soil, which, as Crookston explained, causes an explosion of nutrients (p. 150)? Did the Middle Eastern plants continue to grow abundantly in America? Did the Lehites grow the Jerusalem plants until they could find other food sources, as Brant Gardner suggested?35 John Sorenson noted, “the historical experience of other colonizing parties around the world shows that although imported species may grow well to begin with, they frequently do not do so in the long run.”36 Was the Lehite experience similar to that of millet planted in Yucatan in the 1500s? Millet grew “marvelously well” but then disappeared by the 1900s.37 Or, did the plants from Jerusalem persist for hundreds of years, as Crookston argues? When Europeans settled the Americas, they successfully grew many old-world crops that have persisted until the present day.38 Was the abundant growth of the Jerusalem-adapted plants a miracle?

[Page 357]Plant and animal names

Barley, wheat, and grapes in the Book of Mormon may indeed refer to plants from the Old World growing in Mesoamerica. Wheat and barley, of course, grow well in Mediterranean climates. That climate is obviously a productive area for growing grapes, as well. Crookston asserts that Mesoamerica is a poor place for these plants (pp. 5, 31–37, 42, 50–53, 78–79). Yet, simple internet searches for “does wheat grow in Guatemala?,” “does barley grow in Guatemala?,” and “do grapes grow in Guatemala?” show that all three are grown there today. Presumably they could grow there anciently, too. Sorenson noted that “a substantial number” of pre-Columbian crops from the Old World “have been identified in America,” therefore, the Lehites could have brought such crops to the New World.39 Old-world chickens also are known to have been present, at least in post-Book of Mormon but pre-Columbian times.40 Evidence of other old-world animals in ancient times, such as horses, cows, and goats, has been found.41

Nevertheless, one cannot rule out that an old-world name was given to a new-world plant. An old definition of “grape” is “the berry or fruit of other plants,” with “other plants” referring to non-grape [Page 358]plants.42 This definition may be significant for another reason—it was used between ca. 1400 and 1601, according to the Oxford English Dictionary.43 This is the time of Early Modern English, which has been shown to be the language style of much of the original translated English Book of Mormon.44 Therefore, the one mention of “grape,” by Christ (3 Nephi 14:16),45 could very well have meant the berry or fruit of a Mesoamerican plant and not a reference to Mediterranean grapes. As Spaniards called maize trigo (wheat), prickly-pear cactus fruit fig, and Spondias ciruelo (plum), could the Lehites have named other grains cultivated anciently in Mesoamerica barley and wheat? Example grains that could have received these names are amaranth, huauzontle, chia, setaria (fox-tail millet), and three types of teosinte.46 The same has happened for animals.47 Could barley, wheat, and other old-world ecological and agricultural words have been translated into something English-speaking people in the 1400–1800s would recognize rather than more accurate, but unknown or uncommon, words?48

Stone, cement, and houses

Crookston makes an intriguing point that the Book of Mormon does not mention stone buildings, but, in a book where the emphasis is not history nor how the people lived, is the absence of evidence evidence of absence? Is the absence of a direct discussion of using stone in buildings and homes evidence that the people did not have stone buildings? Sewage and bathing also are not mentioned, but presumably [Page 359]the people had some way to clean themselves and to dispose cleanly of human waste. Many other common human endeavors are also not mentioned. This spurs other questions:

- Was stone not mentioned because it was so common? How often do we modern people leave details out of our diaries and journals because these aspects of our lives are so ordinary?

- Nephi taught his people “to build buildings, and to work in all manner of wood, and of iron,” and other metals (2 Nephi 5:15). Jarom says the people “became exceedingly rich in gold, . . . silver, . . . precious things, and in fine workmanship of wood, in buildings, . . . machinery, . . . iron,” and other metals (Jarom 1:8). If workmanship in wood was separated from buildings, what does that mean? Does working in wood just mean furniture or things that would be inside a home or building, or does it mean making homes of wood? (Or perhaps both?) What does the separate phrase “in buildings” mean? Could that mean buildings made of stone?

- At least some Book of Mormon cities had stone walls. Moroni built walls of stone around cities and elsewhere (Alma 48:8).49 If walls of stone were built, could that also mean buildings were made of stone?

- Although three passages indicate (Mosiah 11:8–10) or may suggest (2 Nephi 5:15, Jarom 1:8) the use of furniture or decorative wood within buildings, only one passage indicates wood was used for constructing buildings (Helaman 3:5–7, 9–11). Two passages indicate wood was used for fortifications (Alma 50:2–3, 53:4). If wood for buildings is only mentioned clearly once, should we make any significance of the fact that stone in buildings is unmentioned?

The Book of Mormon text is not detailed enough to answer these questions. Multiple interpretations are possible, including those Crookston made in Book of Mormon Ecology.

Generally, Mesoamerican cities had stone public buildings and [Page 360]residences built from perishable materials; the public buildings lie in the center surrounded by homes.50 Houses in ancient Mesoamerica were often built from mud materials, namely adobe bricks and wattle and daub construction. Archaeologically, wattle and daub homes are often associated with post molds, remnants of once-buried posts. Adobe construction often lacks post molds. The lighter wattle and daub construction required additional posts to support the roof. Heavier adobe homes did not but required a solid foundation, and foundations of stone, compacted earth, and pottery sherds have been observed.51

Cement construction requires kilns to produce calcining lime, and kilns would need fuel, presumably wood; where did people get wood if trees were scarce? Brant Gardner suggests that Mormon, writing much later and describing his own day, assumed cement was used because of the lack of trees but cement construction caused the deforestation.52 Perhaps other explanations are possible that are consistent with Mormon’s interpretation. Could the people have used another fuel source, such as dried peat? The record says some trees were in the land northward because it says people “spread forth into all parts of the land, into whatsoever parts it had not been rendered desolate and without timber” (Helaman 3:5). Therefore, timber was sparse but not absent (cf. Helaman 3:6–7, 10). Were enough trees there to provide wood for cement production but not enough to build residential and public buildings?

Conversely, the idea that rammed-earth construction was “cement” and found in Mediterranean-America prompts questions. In addition to adobe and wattle and daub, did ancient Americans also use cob or rammed-earth construction? According to Crookston, rammed-earth and cob buildings supposedly can last centuries (p. 139). The Mediterranean-climate regions of North and South America are prone to earthquakes. Is rammed-earth construction safe in such zones? Would rammed-earth buildings survive the frequent earthquakes there?

[Page 361]Exposed bones

One of Crookston’s best questions is how exposed bones could still be around after hundreds of years in a moist environment, but this prompts further questions. Do exposed bones last 400–500 years in Mediterranean climates? Do not exposed bones, at least from individual people or animals, disappear after many years in dry deserts, too? Good preservation seems dependent on rapid burial in peat bogs, dry desert, mud, ice, or other oxygen-deficient environments where decay is slowed. Regardless of climate, what could account for the many exposed bones mentioned in the Book of Mormon? Could piles of bones account for the presence of bones after hundreds of years?53

Wolves

If Alma’s and Jesus Christ’s references to wolves (Alma 5:59–60, 3 Nephi 14:15) referred to an animal the Lehites knew (pp. 27–28, 129–30), evidence suggests the animal was the coyote and not the canine known as a wolf today. Three species of wolf live in North America: the gray wolf (Canis lupus), American red wolf (Canis rufus), and Eastern wolf (Canis lycaon). Subspecies of the gray wolf are known, including the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi). One species, the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus), lives in South America. Historical ranges of these four species do not include Mediterranean southern California, Baja California, or Mesoamerica east of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The range of the gray wolf extended throughout much of North America from the Arctic to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.54 However, the [Page 362]historical range of coyotes (Canis latrans) does include Mesoamerica and North American Mediterranean regions.55 Perhaps the coyote was termed “wolf” by ancient Americans. The coyote is sometimes called the “prairie wolf” or “brush wolf” today, and people often mistake coyotes for wolves. Feral dogs could be another possibility.56

Inconsistent, confusing, weak, and unjustified arguments

The detailed analysis of physical, ecological, and agricultural terms in Book of Mormon Ecology contains many statements that weaken the Mediterranean-American hypothesis. Perhaps oversights in editing, some statements are unclear or are inconsistent with arguments made elsewhere. The relevance of some statements is unclear. Some interpretations are unjustifiably oriented towards Mediterranean-America.

These points should be strengthened or discarded. Without further substantiation, these points add evidence that the sparse ecological words in the Book of Mormon do not allow us to clearly deduce where the people lived. The following sections provide sixteen examples.

The hill north of Shilom

The surroundings of the “hill north of Shilom” are presented inconsistently, and the relevance is unclear. In a discussion about large and small trees near the waters of Mormon, the argument is made that “there were mountains and valleys in the land” (p. 73). The Book of Mormon mentions a “hill north of the land Shilom” (Mosiah 7:5, 16; 11:13) but nothing is said about other hills or mountains. The presence of mountains and valleys near Shilom is certainly possible, but the surroundings could also be flat. Later, Crookston says just that. From the description of the hill north of Shilom, he suggests “the land of Nephi was relatively flat” (p. 164).

Sweet corn

Crookston notes that sweet corn can be grown almost anywhere in [Page 363]the United States, but seeds for sweet corn are grown almost exclusively in Idaho (p. 13). He does not explain how seed produced in Idaho can then, for example, grow well in the different latitude and climate of Florida or the different climate of New York. This seems counter to his assertion that Jerusalem seeds would “grow exceedingly” (1 Nephi 18:24) only in Mediterranean-America—that Wisconsin corn would grow poorly in Texas, and vice versa (p. 6). If the point of growing exceedingly is to “set viable seed” (p. 14) and viable Idaho seeds grow well anywhere in the United States, even in places (Idaho and Florida) with as much or more latitude difference as Wisconsin and Texas and in places with different climates and conditions from Idaho (Florida, New York, Minnesota, and Wisconsin), why could Jerusalem-adapted seeds not grow well in Mesoamerica? Idaho is more Jerusalem-like and Florida more like Mesoamerica.

Pure water

The Land of Helam and Place of Mormon have pure water (Mosiah 18:5; 23:4, 19), and this is implied to be consistent with a Mediterranean location because “pure water was evidently uncommon.” The “fountain of pure water” in Mormon suggests a spring (p. 173, 228, 230–31). The connection to a Mediterranean climate and the importance of “pure water” are unclear.

Wine from grapes

Crookston insists that wine mentioned in the Book of Mormon—at least by Jesus during his visit—must have come from grapes and not another source. “That Jesus used the word wine, just as he had done in Jerusalem, is a persuasive indication that he was speaking about actual wine, and that there was no New World substitute drink involved,” Crookston argues (pp. 79–81). In his discussion of grapes, Crookston states, “the frequent mention of wine in the text clearly suggests grapes” (pp. 52, 60). Crookston acknowledges that pre-Columbian wines in America were made from non-grape plants but then rejects that Jesus would have used such wines for the sacrament. What justification exists that wine for religious events must come from grapes? What justification exists that the mere mention of wine only can mean the drink that comes from grapes?

Vineyards and vines

Related to the argument that sacramental wine must originate with [Page 364]grapes, vineyards and vines are presented as strong evidence for Mediterranean-America and weak for Mesoamerica. Crookston cites scriptural statements “grafted into the true vine” (Alma 16:17), “do men gather grapes of thorns?” (3 Nephi 14:16), and others (pp. 52–53, 60, 75–78, 79–81, 173). No evidence is given why grapes must be the Book of Mormon component of vines and vineyards. No evidence is given why vineyards could not contain or vines be another edible vine plant that is better suited to Mesoamerica than grapes.57

Grapes, olives, and figs

Although Crookston notes that (1) grapes were not documented as being grown by Book of Mormon people (pp. 52, 80), (2) olives are not likely to have been cultivated by Book of Mormon people (pp. 58–59),58 and (3) edible figs are found in subtropical and tropical regions (p. 43), he still argues that the mentions of these fruits mean a strong connection to Mediterranean-America and a weak fit to Mesoamerica (pp. 48, 75–78). Are Old World grapes, olives, and figs the only plants that could be vines or be grown in vineyards in the Book of Mormon? As stated previously, Mesoamerica does have other edible vine plants.

Mesoamerican grapes

Nevertheless, Old World grapes were likely present in ancient Mesoamerica. John Sorenson noted that seeds of European wine grapes (Vitus vinifera) were found in an ancient site in Chiapas.59 In Sorenson’s book, this evidence comes immediately after the evidence of pre-Columbian wines cited by Crookston (p. 80).60 Why the V. vinifera finding was not included in Book of Mormon Ecology is perplexing.

Bread

Bread is unjustifiably labeled a weak fit for Mesoamerica, even though bread made from corn or the word bread referring to “sustenance” is acknowledged to have been possible. Reasons given are that “bread [Page 365]is closely tied to Mediterranean regions because of the prevalence of small grains (wheat and barley)” and because barley was mentioned in the Book of Mormon. Leavened bread is favored by Crookston (pp. 38–41). But, from the Book of Mormon text, we have no idea what kind of bread people ate or used in remembrance of Christ. Certainly, many types are possible.

Beans and squash

Another unjustified and unclear argument concerned beans and squash. Crookston asked why beans or squash was unmentioned in the Book of Mormon if the people lived in Mesoamerica (p. 56). On the other hand, why were beans and squash left out if the people lived in Mediterranean-America? Beans and squash also grow there!

Agricultural claims

Claims about agriculture after the Book of Mormon period are perplexing. Crookston claims that after the Nephites were destroyed at the end of the Book of Mormon that agriculture disappeared (pp. 17–20, 41). This is one argument he makes for the observation that barley, wheat, and old-world domestic animals were not found in America when Europeans first encountered the New World. However, he says, these domesticated animals and plants were found in Book of Mormon times. Conversely, in the same pages, he argues that corn (maize) cannot grow without human intervention. Maize and other crops were grown by indigenous peoples when Europeans arrived in America. Evidence of pre-Columbian agriculture throughout the Americas after the Book of Mormon period is well established, including the growing of a type of barley (little barley) and other plants by the Hohokam in the area where the city of Phoenix is now located.61 As in Book of Mormon times, the indigenous population was large when Europeans arrived. As noted for the Book of Mormon Lamanites, who repeatedly could mount large armies, “only an agricultural base could have supported the extensive population.”62 Hunting and gathering cannot support a large human population. If the people could grow maize, why not wheat and barley, especially if it grew so readily? Put another way, if the Lehite Jerusalem-adapted seeds grew so well in the new land and these crops were grown by the Lehites throughout their recorded [Page 366]Book of Mormon history, why were none of those crops found when Europeans encountered the native American peoples?

Fruit of every kind

The claim of “fruit of every kind” as favoring Mediterranean-America over Mesoamerica is puzzling. Yes, Mediterranean climates are known as biodiversity hotspots, and today plentiful fruits come from Mediterranean regions. Thus, the Book of Mormon statement about “fruit of every kind” fits well there (pp. 47–48). However, subtropical and tropical forests are even greater havens of biodiversity. Fruits also grow well in Mesoamerica. The Book of Mormon statements on fruit does not exclude or favor either region.

Dirt for defense

An argument that “cast up dirt, and the digging of ditches, for defensive purposes, tends not to support the Mesoamerican model” gives no basis for why dirt fortifications could not have been made in Mesoamerica. A reference to another section of the book implies that dirt fortifications were used instead of stone (pp. 140–41). However, one Book of Mormon verse mentions both were used (Alma 48:8). Indeed, ancient Mesoamerican cities are known to have dirt and other fortifications just as the Book of Mormon describes.63

Treeless hills

A weak assertion is that the text is more consistent with a Mediterranean climate because three prominent hills were treeless, and a group of men was thirsty on one of them (pp. 162–66):

- A tower was built on the hill north of Shilom in Lamanite territory, where a group of Nephites had also traveled, made camp, and waited while four of their party went to meet people who lived nearby; the waiting group was hungry, tired, and thirsty (Mosiah 7:5–6, 16; 11:13).

- [Page 367]Part of the Nephite army hid on two sides of the hill Riplah to surprise a Lamanite army (Alma 43:31–35).

- The hill Cumorah (where the Nephites were destroyed) enabled Mormon to see the thousands of dead Nephites after they battled the Lamanites; this hill had to be treeless—otherwise Mormon could not have seen the vast numbers of dead from the hill (Mormon 6:2–15).

However, none of these verses specify that the hills were treeless. If forested, Cumorah and the surrounding area could have been cleared of trees, enabling long views from the hill. Whether or not Riplah was covered with trees is irrelevant. An army could hide with or without trees, and trees would conceal people even better. The hill north of Shilom could also have been cleared of trees, but having trees on that hill would make sense for two reasons. First, the text suggests the hill was prominent and perhaps the only one in the region (Mosiah 7:5–6, 11:13). If so and the hill was treeless, why build a tower if the vantage enabled one to see far? If trees were present on the hill, a tower would enable one to see above the trees. Second, trees would enable the Nephite party to be more easily concealed. If the party stayed on the hill for fear of being discovered by Lamanites, and no water or food sources were on the hill, that could also explain their hunger, thirst, and fatigue (Mosiah 7:16). The text says they did have to wait at least two days (Mosiah 7:5–16). Crookston’s interpretation may be correct, but it is not the only valid one and is not confirmed by the text.

Poisonous serpents

An additional weak argument is that the plague of poisonous serpents in Jaredite times (Ether 9:31–33, 10:19) is a weak fit for Mesoamerica. Two justifications were given:

- The incident was imagined to have occurred in Mediterranean-like open country where snakes are more visible than in forests.

- Hugh Nibley noted three similar incidents that occurred anciently in the Middle East.

Therefore, Crookston reasoned that the serpent incident is a weak fit for Mesoamerica and a better fit for Mediterranean-America (pp. 122–23). However, venomous snakes live in both places. Why is visiblity of snakes in dry, open country more favorable than snakes that may be harder to see in a forest? Less visible snakes would probably[Page 368] be more frightening to the Jaredites. Again, both Mesoamerica and Mediterranean-America fit the Book of Mormon text.

Hiding among small trees

To justify calling “a thicket of small trees” a forest, the argument was made that the thicket of small trees at the waters of Mormon could hide 450 people (p. 71). The text says that only Alma hid in the thicket of small trees (Mosiah 18:5). We do not know if the entire group could hide there. The text suggests they could not because the group fled into the wilderness after being discovered (Mosiah 18:32–35).

Renewal of fruit growth