Authors

David Eddington

Abstract: Numerous discussions of the similarities between the LDS temple endowment and Masonic rites exist, which give the impression that the two overlap considerably. Rather than focus on the similarities themselves, this paper seeks to quantify how much the two rites overlap by performing a textual analysis. In the first section, the named entities, clothing, props, and participants in the ceremonies are compared. In the second section a line-by-line comparison identifies similar wording, structure, and meaning in the text, which results in a 10% to 17% overlap between the texts. The third section involves comparing sequences of one to five words in the text. For this task, three additional texts were included for comparison: portions of the Pearl of Great Price, the Odd Fellows rite, and the mystagogical catechesis (an initiation into mysteries). In some instances, comparisons indicate more similarity between the Masonic and Odd Fellows ceremonies than between the LDS endowment and the Masonic rite.

The relationship between Masonry and the LDS temple endowment has generated a great deal of interest in the LDS community, among friends of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and in anti-LDS circles. Numerous publications discuss the similarities between the endowment ceremony and Masonry.1 The [Page 312]extant similarities were explained by early members of the Church as evidence of an early ceremony that arrived in a corrupted form in Masonry, then restored by revelation to Joseph Smith.2 Yet others explain many of the similarities by pointing to their existence in sources that predate both the Masonic rite and the endowment.3

I recognize that the similarities are undeniable, and my purpose is not to further nor to dispute any of those arguments. One way to approach the two rites and their similarities is to acknowledge that they employ similar frameworks, but for very different purposes. Kearney describes it this way: “the temple ritual teaches us about our relationship to deity the Masonic Lodge is teaching us about our relationship to our fellowmen.”4 As useful as this explanation may be, it still leaves the question regarding how similar the two ceremonies truly are. Seaich asserts, “It is particularly noteworthy that of all the extensive Masonic ritual, which occupies more than two-hundred double-columned pages in Richardson’s Monitor of Freemasonry, the Prophet accepted as genuine only that which might fill a single page in the same format, even correcting it in major points.”5 While this provides a rough estimate of overlap, Buerger notes that the only way to accurately quantify the degree of similarity would be to closely compare the documents on a passage-by-passage basis, which can be difficult because “both ceremonies are open only to members in good standing who have made personal covenants not to divulge the proceedings.”6 In this paper I attempt to take up the challenge laid [Page 313]down by Buerger, and to do so in a manner that is respectful of both parties’ confidentiality. I will quantify the similarities of the two rites by comparing them textually.

From the onset, comparing the texts of the temple endowment and the Masonic rite presents a number of challenges. As noted above, they both contain elements that participants promise not to share with others. In order to respect those instructions, I will not discuss these elements directly, and I will not provide details of all of the data used to examine the similarities. Secondly, both ceremonies have evolved and exist in different versions, and need to be placed on the most equal footing possible. This is why I have chosen versions that come from similar places and time periods; more specifically the Masonic rite as practiced in the late nineteenth century in the United States (as described by Duncan), and the early twentieth century temple endowment described by Paden.7

This approach may cause some confusion to modern members of the Church, because elements are mentioned in this paper that do not match the current version of the endowment ceremony. But comparing both rites in their versions closer to the time and place of Joseph Smith supports one of my purposes—demonstrating the unlikeliness of Joseph Smith having appropriated wholesale from Masonic rites.

Paden’s version of the LDS endowment lacks some elements related to the Creation, therefore I filled in by using other online sources, thus allowing me to more faithfully compare the rites. Also, Duncan’s description of the Masonic rites required some adjustment, because he not only included the three degrees of masonry, but the higher degrees as well (such as Mark Master, Past Master, Most Excellent Master, and Royal Arch). Because Joseph Smith had only been initiated into the first three degrees of Masonry before the endowment was created,8 I have excluded the higher degrees in this comparative study.

Of course, one could argue that other versions of the rites would be better suited to the task of comparison. However, one crucial aspect [Page 314]of the texts selected is that they are available in electronic form, which is particularly important for carrying out the textual analyses.

Named Entities, Clothing, and Props

One way in which the two rites may be compared is by examining the named entities in the ceremonies, the props that are used, and the clothing that is worn. In each ceremony more than one role may be assumed by a single person, but all roles are given individually. I will do this three-fold examination before moving on to the more quantitative parts of the analysis. The examination is best visualized through a series of two-column tables, with the Masonic rite in the left column and the LDS endowment in the right. In each column, information is arranged in alphabetic order; there is no correlation between left and right items on each row.

Table 1 lays out all of the roles and participants. In each ceremony there is a candidate who goes through an allegorical journey. In the Masonic tradition the candidate takes on the role of Hiram Abiff, while endowment participants take on the role of Adam or Eve. The Worshipful Master, Senior Warden, and Junior Warden preside over the Masonic rite, while in part of the endowment the roles of God’s messengers are portrayed by characters who represent the New Testament apostles Peter, James, and John. Beyond this, one is hard pressed to find potential parallels, unless we consider the present-day temples in which the person who serves at the recommend desk (the entrance into the temple) finds his counterpart in the Tyler (the lodge’s outer guard, who prevents entry by unauthorized individuals).

In the endowment, references to people are strictly limited to deity and the participants in the ceremony (table 2). This contrasts starkly with the Masonic rite, which includes many mentions of biblical people(s) as well as generic references to a number of others. A similar state-of-affairs occurs with the places mentioned. The endowment discusses the heavenly bodies formed during the Creation, the Garden of Eden, and the kingdoms in the world to come. In contrast, the Masonic rite references rooms in the Temple of King Solomon and in Masonic Lodges, along with several biblical places (table 3).

Perhaps the most apparent similarities between the two rites are the use of ceremonial clothing (table 4). A prominent difference is that the Masonic ceremony uses quite a few props, including a number of tools that are absent in the endowment, with the exception of the compass and square that in the endowment appear only symbolically, [Page 315]not as actual props. Endowment props include oil and water, which are used in the washing and anointing portion of the endowment. At a time, there was also a sword in the endowment, which no longer plays a role. Missing from Paden’s description of the endowment in the early twentieth century is the Bible or other scriptures on the temple altar. Whether this is due to oversight or changes in the ceremony is not known.

Overall, what should stand out from this comparison is the different focus of each rite. The endowment deals with the creation of the earth, the earth as a proving ground for God’s children, and the kingdoms that will exist in the post-mortal existence. On the other hand, Masonry began as a trade guild, and their rite emphasizes the purported history of their craft in the building of the temple of King Solomon, as well as the relationship of the members of the guild to each other. For this reason, the tools of the mason trade comprise the principal symbolic elements of their ceremony.

Table 1. Participants in the rites.

| Masonic Participants | Endowment Participants |

|---|---|

| Candidate | Adam or Eve |

| Captain | Officiator |

| Conductor | Brother/brethren (men in attendance) |

| Fellow Crafts | Candidate |

| Grand Secretary | Elohim (Father) |

| High Priest | Eve |

| Hiram Abiff | James |

| Jubela | Jehovah (Jesus, Lord, Master, Savior, Son) |

| Jubelo | John |

| Jubelum | Lucifer (Devil, Tempter) |

| Junior Deacon | Michael |

| Junior Grand Warden | Peter |

| King Solomon | Preacher |

| Masons | Sisters (women in attendance) |

| Secretary | This people |

| Senior Deacon | |

| Treasurer | |

| Tyler | |

| Worshipful Master |

[Page 316]Table 2. References to people(s) in the rites.

| Masonic References | Endowment References |

|---|---|

| Biblical People(s) | |

| Aaron | Adam |

| Children of Israel | Christ |

| God (known by many names, such as Deity, Grand Warden of Heaven) | Devil |

| Hiram King of Tyre | Elohim |

| Jephthah | Eve |

| Jeremiah | God |

| King Solomon | Holy Ghost |

| Men of Gilead | James |

| Moses | Jehovah |

| Saint John the Baptist | Jesus |

| Saint John the Evangelist | John |

| Tribe of Judah | Lucifer |

| Michael | |

| Peter | |

| Generic People | |

| Atheist | This people |

| Brother | |

| Cowans | |

| Eavesdroppers | |

| Fool | |

| Friend | |

| Impostors | |

| Madman | |

| Neighbor | |

| Old man | |

| Orphans | |

| Widows | |

| Woman | |

| Young man | |

[Page 317]Table 3. References to places in the rites.

| Masonic References | Endowment References |

|---|---|

| Places | |

| Holy of Holies/Sanctum Sanctorum | Celestial world |

| King Solomon’s Temple | Earth |

| Lodge of Fellow Crafts | Garden of Eden |

| Lodge of the Saints John of Jerusalem | Heaven |

| Middle chamber | Hell |

| Lone and desolate world | |

| Terrestrial kingdom | |

| Biblical Places | |

| Ethiopia | |

| Hermon | |

| Israel | |

| Jerusalem | |

| Joppa | |

| Lebanon | |

| Mount Moriah | |

| Red Sea | |

| River Jordan | |

| Succoth | |

| Valley of Jehoshaphat | |

| Zeredatha | |

| Zion | |

| New World Places | |

| State (within the US) | This nation (USA) |

| United States of America | |

| Celestial Bodies | |

| Celestial Lodge | Earth |

| Earth | Heavens |

| Heavens | Moon |

| Moon | Stars |

| Stars | Sun |

| Sun | World |

| World | |

[Page 318]Table 4. Clothing and props used in the rites.

| Masonic Rite | Endowment |

|---|---|

| Clothing | |

| Apron | Apron |

| Blindfold | Cap |

| Hat | Garment |

| Sash | Robe |

| Slipper | Sash |

| White gloves | Slippers (moccasins, sandals) |

| Yoke | Veil |

| Props | |

| Cable-tow | Hymn book |

| Candles | Mallet |

| Canvas | Oil |

| Coin | Sword |

| Compass | Water |

| Gavel | |

| Holy Bible9 | |

| Level | |

| Mallet | |

| Plant | |

| Plumb | |

| Rod | |

| Rope | |

| Setting-maul | |

| Square | |

| Stairs (actual or symbolic) | |

| Sword | |

| Trowel | |

| Twenty-four-inch gauge | |

[Page 319]Conceptual Comparison

I now move on to the principal goal of quantifying the degree of similarity. The first comparison below is conceptual, by parsing out each sentence of the endowment. I have added some instructions that are not spoken during the endowment, when relevant to the comparison. This yielded 448 sentences, each of which was compared to the Masonic rites by searching for similarities in wording, structure, or meaning.

In making the comparisons, I tried to be as liberal as possible. For example, there is no direct correlation between the washings and anointings in the endowment and the Masonic rites. However, the latter cites Psalm 23:5, “Thou anointest my head with oil.” Therefore the sentence in the endowment regarding anointing was marked as having a similarity with the Masonic rite. A second example of liberality in comparisons has to do with the fact that in each ceremony there are three principal characters: Elohim, Jehovah, and Michael (or Peter, James and John) in the endowment, and Worshipful Master, Senior Warden, and Junior Warden in the Masonic rite. A third example involves the different positioning of clothing, wherein the different ways of folding the Masonic apron has its parallel in the different ways the robe is worn in the early twentieth-century endowment. Also, every reference to a single concept—such as new name—is counted according to the number of times it appears. Table 5 provides additional examples of contextual similarities.

Table 5. Examples of conceptual and textual similarities.

| Masonic Rite | Endowment |

|---|---|

| And God said, Let there be light, and there was light. | Call the light “day,” and the darkness “night.” |

| Has it a name? | Has it a name? |

| (Three taps with the gavel) | (Three taps with the mallet) |

| The sign of ___ of a Master Mason, which is done by ___. | The sign is made by ______. |

| Will you give it me? | Will you give it to me? |

| The five points of fellowship are ___. | These are ___. |

| (Many references to Masonic apron.) | What apron is that you’re wearing? |

As stated above, these “conceptual” comparisons are designed to quantify the similarity between the two rites. Of the 448 sentences in the endowment, seventy-seven have correlates in the Masonic rite, [Page 320]according to this liberal interpretation of similarity. That is to say, there is a 17.2% overlap in the conceptual content of the two ceremonies. Of course, this percentage is based on making all comparisons, even when the similarity is somewhat tenuous, such as making the parallel between Jehovah, Elohim, and Michael in the endowment and Worshipful Master, Senior Warden, and Junior Warden in the Masonic ceremony. The number also includes counting multiple instances of the same point of similarity.

A different measure of conceptual similarity can be calculated by being less generous in determining what counts as “similar.” To do this, the twenty-five lines that had duplicate entries were deleted (for example, four of the five instances of it has, and five of the six cases of What is that?). Also deleted were what I considered the most tenuous similarities. The result is that only forty-one of the concepts in the remaining 423 lines of the endowment, that is to say 9.7%, have correlates in the Masonic rite. The present version of the temple ceremony (2023) has been modified in a way that six of the forty-one similar concepts no longer exist, thus lowering the conceptual similarity to 8.3%.

Textual Comparison

Another way of gauging similarity is by direct textual comparison, that is, by examining the words and sequences of words in the texts. However, if we find, for example, a 20% similarity between the texts, what does that really indicate? Any two randomly chosen documents will likely have a certain degree of overlap. For this reason, a more fruitful approach is to examine other related documents in order to have a more significant point of comparison. To this end, I chose three additional texts.

The first text, one that is very similar to the endowment, is found in the creation accounts in the Pearl of Great Price consisting of chapters 1–5 of the Book of Moses and chapters 4–5 of the Book of Abraham. The second document is an excerpt of lectures written by Cyril of Jerusalem10 in about 350 A.D. It comprises lectures 19–23 known as [Page 321]the mystagogical catechesis. Nibley points out that these lectures to new initiates have a great deal in common with the endowment.11

The LDS endowment and Masonic rites are both initiation ceremonies and need a point of comparison with another initiation ceremony, especially one that like the endowment, has noted similarities to the Masonic rite. I selected the 1909 Odd Fellows rite from the United States.12 Included in the Odd Fellows rite are the texts from the lodge degrees and the first to third encampment degrees.

Textual Preparation

As with the previous comparisons, only the first three degrees of Masonry were included, and the orders of business and names of candidates in Duncan’s account of the Masonic rite were also eliminated. All of the texts were prepared for comparison by removing headers, verse numbers, footnotes, bibliographic material, and so forth. In the rites, only text that is meant to be spoken was included, thus deleting descriptions and non-verbal instructions.

Also, the words in the documents were converted to lower-case, and punctuation was eliminated. One version of the texts was created by removing all “stop words,” which are function words such as the, an, yet, for, to, and, are, is, that, why, it, and so forth. This is important when comparing the vocabularies used in each document, because these words are of little relevance. Another version of each text was created that retained the stop words. From these versions, each of the four documents were divided into various N-grams (sequences of the same contiguous words)—in this case, sequences of two to five words. For example, the sequence of words the name of the Lord contains the bigrams (two same contiguous words) the name, name of, of the, and the Lord. Plus, it contains the trigrams the name of, name of the, of the Lord, the 4-grams the name of the, name of the Lord, and the 5-gram the name of the Lord.

[Page 322]Vocabulary Comparisons

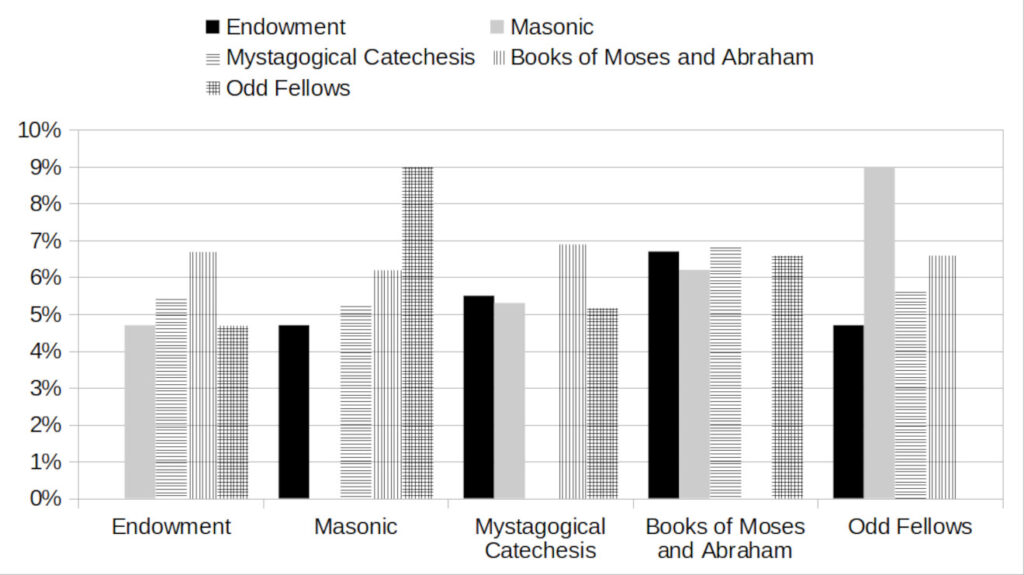

The lists of individual words (minus the stop words) were compared across the four documents, calculating the percent of vocabulary each text shares with the other three texts. In figure 1, the four bars on the left indicate how much vocabulary the endowment shares with the other four texts. The order that each set of four bars appears in the graph is identical, but gaps appear because texts are not compared to themselves.

Figure 1. Percent of common vocabulary.

In the case of the endowment, it has more words in common with the books of Moses and Abraham (18.4%) than it does with the other three documents. Also, the endowment shares 10.8% of its vocabulary with the Masonic text, and so forth. The next set of four bars show that the Masonic text overlaps most with the Odd Fellows text (24.7%). And the mystagogical catechesis shares the highest percent of its vocabulary with the books of Moses and Abraham (16.9%).

N-Gram Comparisons

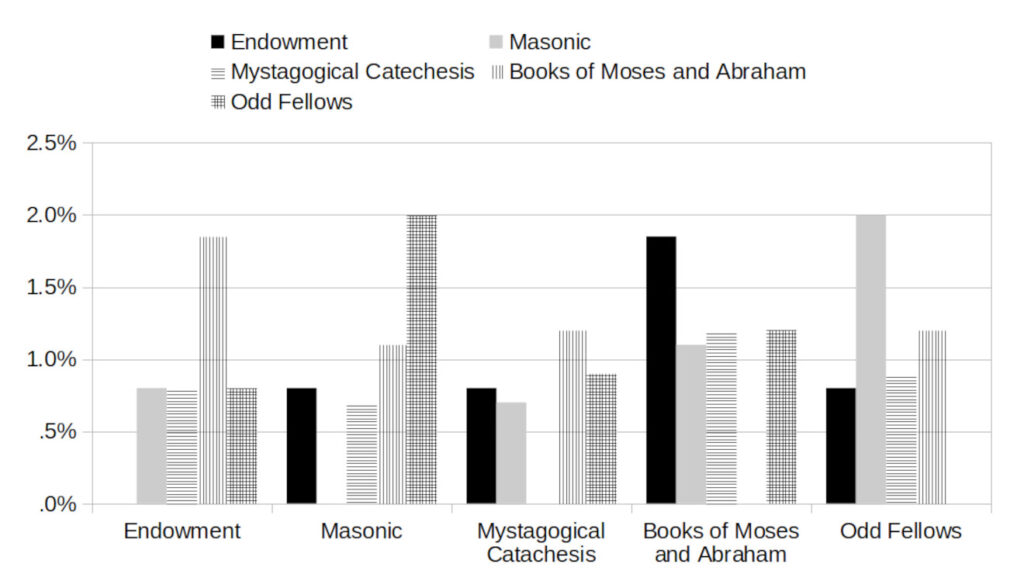

For the N-gram comparisons, the stop words were included, meaning that sequences such as to the, what does it, and to make use of it, were counted. As figure 2 indicates, the endowment and the books of Moses and Abraham have the most bigrams in common, while the Masonic and Odd Fellows texts are more similar in this regard. The [Page 323]mystagogical catechesis has more bigrams in common with the text from the books of Moses and Abraham.

Figure 2. Percent of bigram overlap.

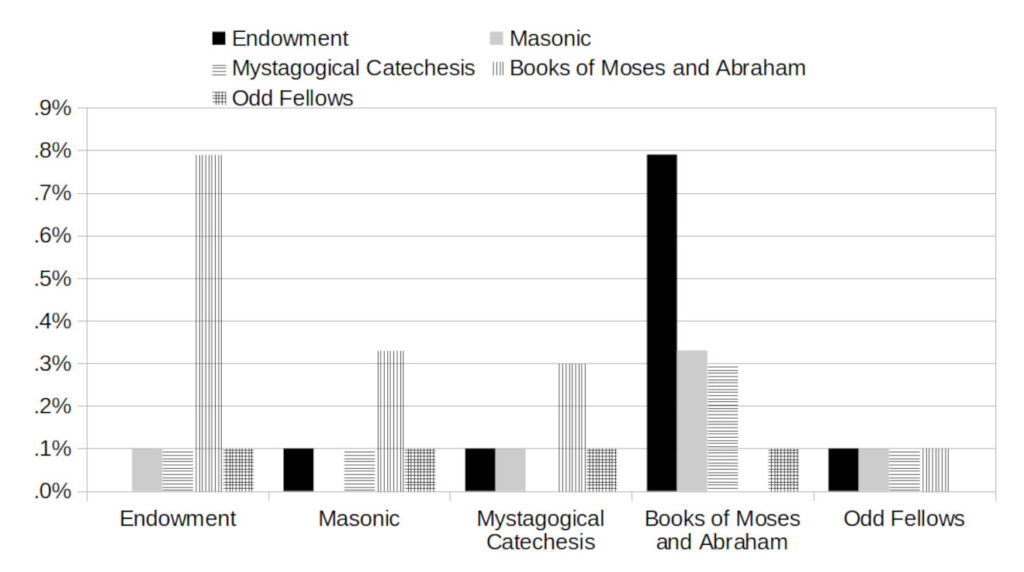

The percentage of words in common decreases drastically as the number of words in the N-gram increases (figures 3–5), and the general trend is apparent in the figures. The endowment shares more N-grams with the books of Moses and Abraham, the Masonic and Odd Fellows rites are most similar to each other, while the mystagogical catechesis is most similar to the books of Moses and Abraham.

Figure 3. Percent of trigram overlap.

[Page 324]

Figure 4. Percent of 4-gram overlap.

Figure 5. Percent of 5-gram overlap.

Conclusions

Most of the literature that compares the temple endowment and Masonic rites tends to emphasize their similarities. Without a more thorough comparison, such discussions may give the false impression of massive plagiarism on the part of Joseph Smith. Having quantified the degree of similarity by examining early versions of the two rites—in terms of the people, places, participants, and objects—clearly [Page 325]indicate that different narratives are utilized in the Masonic lodge and the LDS temple endowment.

The commonalities in tables 1–4 are primarily limited to some items of clothing, references to heavenly bodies, and the existence of the square and compass.

Some similarities are evident in the texts themselves, as shown in the line-by-line comparisons of the two ceremonies in terms of structure, wording, and meaning. This approach allows us to quantify the degree of similarity, yielding a potentially more accurate measure. The overlap between an early version of the endowment and a nineteenth century version of the Masonic rite reaches about 10% to 17% (depending on how liberal or restrictive the definition of similarity). It is worth noting that many of the common aspects between the two ceremonies no longer exist in the present version of the LDS endowment.

A comparison of vocabulary and N-grams between two documents is not particularly revealing by itself, because any two texts will demonstrate some degree of similarity. Therefore, in the N-gram portion of comparison, three additional texts were included that have a similar scope to the Masonic and temple ceremonies: the creation account in the books of Moses and Abraham, the lectures of Cyril of Jerusalem (known as the lectures to the newly initiated or the mystagogical catechesis), and the Odd Fellows rite.

In the vocabulary comparison and in the comparisons of N-grams, the endowment matches most closely with the books of Moses and Abraham, as one may expect. The second most similar text to the endowment is the mystagogical catechesis, as measured by vocabularies and bigrams.

Identifying the two most similar texts according to 3- to 5-grams, the Masonic text aligns most closely with the Odd Fellows rite in three of the five analyses and with the books of Moses and Abraham in the remaining two. All five of the second-place comparisons with the Masonic text are with the books of Moses and Abraham.

While most analyses focus exclusively on the handful of similarities between the LDS endowment and the Masonic rite, they do not compare the entirety of those ceremonies. A more complete comparison, on the other hand, highlights the fact that the commonalities comprise a very small proportion of the rites. The purposes of the two ceremonies are different, and the story told in each is unique. The small [Page 326]portion that they do share involves the symbolic way in which certain elements of the two rites are presented.

David Eddington is a retired professor of linguistics at Brigham Young University. His research focuses on quantitative and experimental approaches to the phonology and morphology of Spanish and English, as well as on Utah dialect. He presently lives on the Mediterranean coast of Spain with his wife, Silvia.

3 Comment(s)

Theron Stanford, 10-04-2025 at 4:53 am

“The examination is best visualized through a series of two-column tables, with the Masonic rite in the left column and the LDS endowment in the right. In each column, information is arranged in alphabetic order; there is no correlation between left and right items on each row.”

Then don’t use tables with perfectly aligned rows and horizontal guidelines, which confuse the reader. Tables add visual meaning. Just present two lists side by side, at least for Tables 1 through 4.

Steve Mordecai, 09-28-2025 at 9:22 am

Thank you! A most interesting paper. My brother is an Odd Fellow and I am a convert. Neither one of us had any religious affiliation. I knew very little of the Odd Fellows and my brother very little of the “Mormons”. Now we have a little more in common, thanks to your paper.

Muchisimus gracias hermano.

Corina, 09-26-2025 at 2:24 pm

Muy buen estudio y análisis. Los mitos se enfrentan a los hechos y la realidad.